Reference & Value Semantics

The intent of this entry is to review the differences between reference & value types, and leverage our understanding to optmize the performance of our applications. I reckon it’s probably most appropriate, as a warm up to this discussion, to first revisit the fundamentals from WWDC 2016, Session 416 - Understanding Swift Performance.

Reference Types

- Reference types are shared rather than copied

- Memory for reference types are allocated on the heap

- Reference types do not come with compiler-generated memberwise initializer

- Reference types can support inheritance

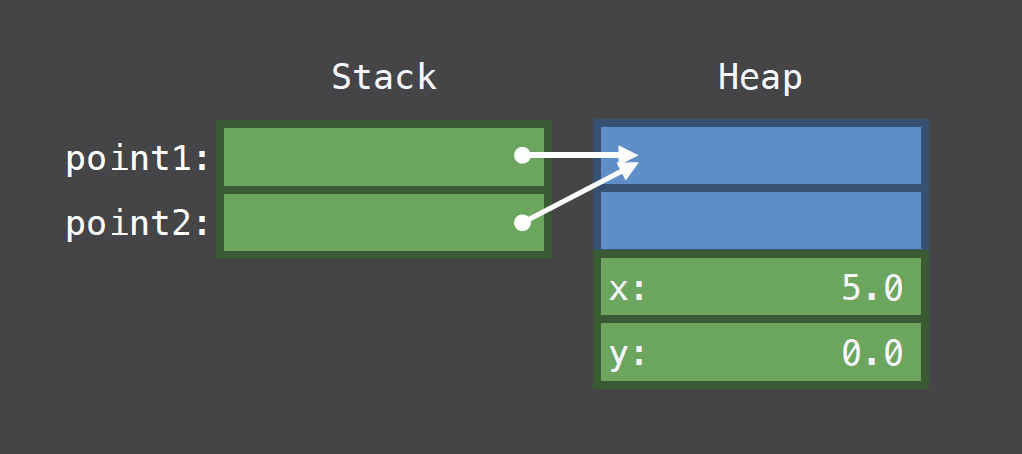

Below’s a depiction of how reference types are allocated in memory.

Image from Presentation Slides, WWDC 2016, Session 416

// Define reference type Point

class Point {

var x, y : Double

// Reference types don't come with memberwise initializer

// We need to explicitly declare one

init(x: Double, y: Double) {

(self.x, self.y) = (x,y)

}

}

// 1. Allocate memory for instance of Point on the heap with (x,y) = (0,0)

// 2. Allocate memory for point1 on the stack storing address to the Point object on the heap

let point1 = Point(x: 0, y: 0)

// Allocate memory for point2 on the stack storing address to the Point object on the heap

var point2 = point1

// point2.x is 5, and point1.x is now also 5

point2.x = 5

From the image above, it appears that the memory block allocated on the heap is more memory than is necessary to accommodate variables x & y. This is because an excess of memory is required to manage reference types.</br> To name a subset here:

isapointer - Reference types support inheritance, thus we need a way to walk the inheritance hierarchy in dynamic binding- Reference counter - Heap memory needs to be recycled when it’s no longer in use, thus tracking active references to the memory is important

Below is a snippet simulating (simplified) compiler generated logic from the code above to illustrate what’s really going on behind the scenes:

// Retain/release imeplementations

func retain<T: ReferenceCounting>(_ object: T) {

object.refCount+=1

}

func release<T: ReferenceCounting>(_ object: T) {

object.refCount-=1

}

// All reference types implicitly support reference counting

protocol ReferenceCounting : class {

var refCount : Int { get set }

}

extension Point : ReferenceCounting {}

class Point {

// Reference types have memory allocated for reference counting

var refCount : Int

var x, y : Double

init(x: Double, y: Double) {

refCount = 1

(self.x, self.y) = (x,y)

}

}

let point1 = Point(x: 0, y: 0)

var point2 = point1

// refCount of the Point object is incremented when point2 makes reference to it

retain(point2)

point2.x = 5

// refCount of the Point object is decremented when point1 is popped off the call stack,

// and decremented again when point2 is popped off the stack.

// Now refCount of the Point object is now 0, and can be safely recycled.

release(point1)

release(point2)

Value Types

- Value types are copied rather than shared

- Memory for value types are allocated on the call stack

- Value types come with compiler-generated memberwise initializer

- Value types do not support inheritance

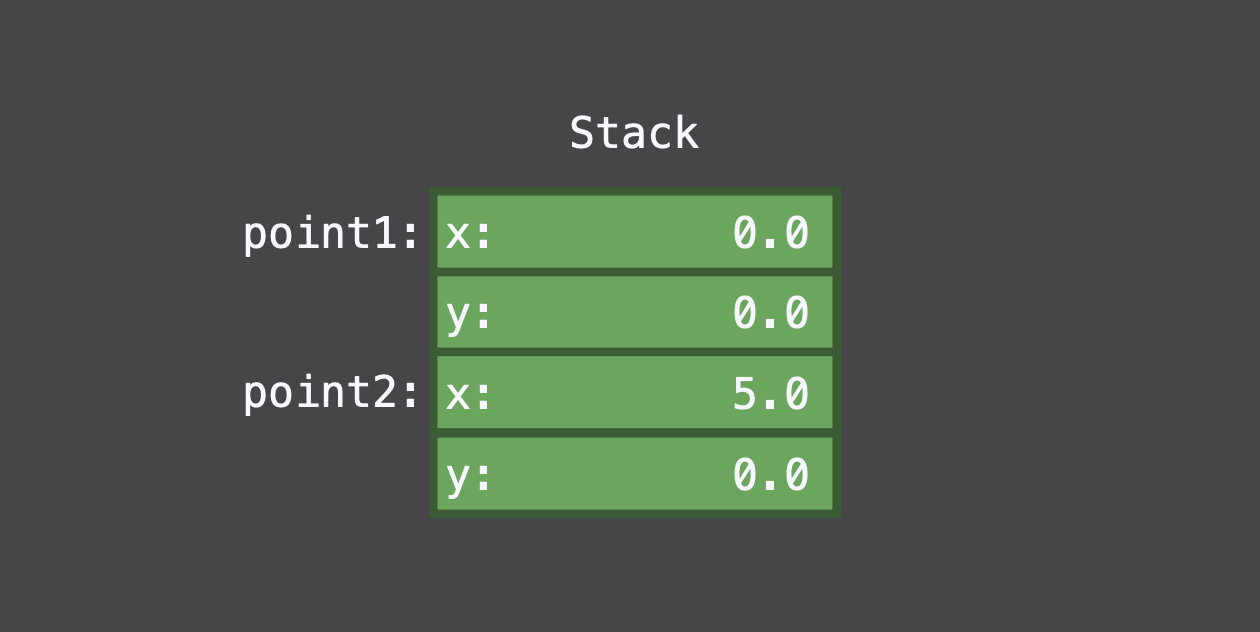

Below’s a depiction of how value types are allocated in memory.

Image from Presentation Slides, WWDC 2016, Session 416

// Define value type Point

struct Point {

var x, y : Double

}

// Allocate memory for point1 on the stack & initialize (x,y) = (0,0)

let point1 = Point(x: 0, y: 0)

// Allocate memory for point2 on the stack & initialize (x,y) = (point1.x, point1.y)

var point2 = point1

// point1.x is 0, point2.x is 5

point2.x = 5

The example from above is naive enough, but not very interesting. Value types with value type properties are allocated on the stack - we all know that. What about value types with reference type properties?

Value Types with Reference Type Properties

To understand what really happens when we have value types with reference type properties, we’ll try things out for ourselves.

// Name Type

// Define reference type Name

final class Name {

var firstname, lastname : String

init(firstname: String, lastname: String) {

(self.firstname, self.lastname) = (firstname, lastname)

}

}

extension Name : CustomStringConvertible {

var description: String {

return "\(firstname) \(lastname)"

}

}

// Person Type

// Define value type Person with reference type property Name

struct Person {

public let name : Name

// Accessors for the Person's firstname & lastname

public var firstname : String {

get { return name.firstname }

set { name.firstname = newValue }

}

public var lastname : String {

get { return name.lastname }

set { name.lastname = newValue }

}

}

// Person johnDoe has firstname "John", lastname "Doe"

let johnDoe = Person(name: Name(firstname: "John", lastname: "Doe"))

// Create a new Person copy from johnDoe - Person janeSmith

var janeSmith = johnDoe

// Update janeSmith's first & last name

janeSmith.firstname = "Jane"

janeSmith.lastname = "Smith"

// This outputs "Jane Smith", even though we expect johnDoe's name to be "John Doe"

print(johnDoe.name)

What’s really happening here is that we’ve indeed created 2 instances of Person on the stack, but these 2 instances in fact share the same reference of the Name object that’s created on the heap. This is definitely not what we want, so how do we fix it?

Copy-On-Write

Getting Value Semantics from Mixed Types:

The idea with copy-on-write is this: having multiple objects referencing the same reference type object is fine - as long as none of these references modify the object. When the object is modified though, we’d want to create a new copy of the object. Here’s how we can use copy-on-write to avoid problems with value types wrapping reference types.

// Name Type

// Define reference type Name

final class Name {

var firstname, lastname : String

init(firstname: String, lastname: String) {

(self.firstname, self.lastname) = (firstname, lastname)

}

}

extension Name : CustomStringConvertible {

var description: String {

return "\(firstname) \(lastname)"

}

}

// Person Type

// Define value type Person with reference type property Name

struct Person {

public private(set) var name : Name

// Accessors for the Person's firstname & lastname

public var firstname : String {

get { return name.firstname }

set {

// Check to see if there are other references to name,

// if there are, create a new Name object assign the name reference to it

if !isKnownUniquelyReferenced(&name) {

name = Name(firstname: newValue, lastname: name.lastname)

return

}

name.firstname = newValue

}

}

public var lastname : String {

get { return name.lastname }

set {

// Same check is done here as for firstname, but here we assign the new value to the lastname property

if !isKnownUniquelyReferenced(&name) {

name = Name(firstname: name.firstname, lastname: newValue)

return

}

name.lastname = newValue

}

}

}

// Person johnDoe has firstname "John", lastname "Doe"

let johnDoe = Person(name: Name(firstname: "John", lastname: "Doe"))

// Create a new Person copy from johnDoe - Person janeSmith

var janeSmith = johnDoe

// Update janeSmith's first & last name

janeSmith.firstname = "Jane"

janeSmith.lastname = "Smith"

// This now outputs "John Doe", as desired

print(johnDoe.name)

Optimizing System Performance:

We learned how to use copy-on-write to get value semantics from mixed types, but uses of copy-on-write go far beyond. For example, Swift’s Array implementation reduces memory footprint by intentionally wrapping value types inside reference types, using copy-on-write (lazy copy) to avoid excessive memory allocation of large value type objects. Can you imagine a huge chunk of memory being allocated on the stack everytime a large array is assigned or passed into a function call? Just thinking about it makes my spine tingle. Anyhow, the template is very similar to that we’ve laid out earlier.

// Reference type Ref is a value type wrapper

final class Ref<T> {

var val : T

init(_ v : T) { val = v }

}

struct ValueType<T> {

// The ref variable holds the reference type Ref,

// and wraps the value type on initialization

var ref : Ref<T>

init(_ x : T) { ref = Ref(x) }

var value: T {

get { return ref.val }

set {

// If reference to ref is not unique, we want to create a new object

if !isKnownUniquelyReferenced(&ref) {

ref = Ref(newValue)

return

}

// Otherwise just use the existing reference

ref.val = newValue

}

}

}

Boxing

If you’ve overheard people talking about a technique called boxing, it is the idea of wrapping value types in reference types so that value types can be passed around with very little incurred memory footprint (where appropriate). This is the exact concept we’ve discussed earlier; the only difference is nomenclature. I’m listing it here for the sake of completeness.

// Define value type Dog

struct Dog {

let age : Int

}

// Box is a reference type wrapping a value type

final class Box<T> {

var value: T

init(value: T) {

self.value = value

}

}

// Now we can pass value type Dog around as a reference

class Container {

let box: Box<Dog>

init(_ dog: Dog) {

box = Box(value: Dog(age: 2))

}

}

Wrapping Up

Performance Metrics:

Here are some of the questions worth asking when deliberating between using reference types versus value types:

Is memory allocated on stack or heap?

- Stack - memory allocation is fast

- Decrement & increment the stak pointer to allocate & deallocate memory.

- Heap - memory allocation is slow

- Need to search for contiguous blocks of memory of sufficient size, potentially de-fragmenting memory blocks to satisfy the allocation

- House-keeping post deallocation

- Thread-safety overhead (locking mechanism) with heap access

How much reference counting overhead is incurred at run-time?

- Reference counting needs to be atomic, making it an expensive operation

- A good tradeoff is a balance between reasonable memory footprint & minimal reference counting

What portion of method calls on instances are dynamically dispatched?

- Static dispatch allows for optimization at compile time such as code inlining

- Minimal runtime dispatch translates to better system performance

- Prioritize value types over reference types if possible, alternatively declare reference types as final if they are not meant to be subclassed